More than half of female endurance athletes and one-third of women who exercise more than two hours a week may not be eating enough food to meet the energy demands of their sport.

Over time, this lack of fuel can affect women’s health, causing menstrual cycle dysregulation, increased illness and injury, gastrointestinal symptoms, metabolic and cognitive changes, and poor athletic performance. Other more serious health issues such as osteoporosis may arise later in life.

Two University of Victoria (UVic) graduate students have received prestigious Mitacs awards to research the cognitive and cerebrovascular effects of an understudied and little-known condition called relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs).

Athletes’ experience informs research

For Emma Skaug and Ella Lane, both interdisciplinary students in the schools of Medical Sciences and Exercise Science, Health and Physical Education, their research projects stem from personal experience.

Both have experienced the debilitating effects of REDs. Skaug is a professional triathlete and former para-triathlon guide who assisted in winning the bronze at the 2022 Commonwealth Games women’s para-triathlon race. Lane is a member of the UVic women’s national cross-country championship team.

Skaug started training for triathlon when she was 14 years old. At 16, she became concerned that she hadn’t started menstruating. A family physician assured her it was normal for an active young woman to not have a cycle.

I started falling prey to common thought patterns surrounding what my body needed to look like to be successful. I had no education on the nutrition I required for the amount of training I was doing.”

—Emma Skaug, PhD student

Two years later, Skaug was at the Triathlon Canada National Training Centre in Victoria, where a physician told her she was not eating enough. The moment was a revelation for Skaug, who was frequently sick, injured and had trouble increasing her training volume.

“I ate more at every meal throughout the day, and after four months I got a menstrual cycle for the first time,” she says. “I was worried about what my future in sport would look like if I wasn’t able to get healthy.”

Lane similarly recalls not consuming enough calories to fuel a demanding training schedule as a competitive swimmer in high school.

She was growing but losing weight—and eventually she stopped menstruating. A doctor similarly told Lane not to worry. In the summer, when Lane had time off from swimming, her menstrual cycle would return.

“I really did have an association that when I’m fit and active, I don’t have a menstrual cycle,” she says.

Over time, Lane became chronically sore, exhausted and prone to panic attacks while swimming. Her performance suffered. Lane quit swimming, and it wasn’t until she started running competitively at university that a coach told her she needed to fuel her body better.

“I look back on how much I invested in that sport, how much of my self-worth was tied into swimming,” Lane says. “When I was failing, it felt like it was my fault.”

Women-led research fills gap

Today marks the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, and Skaug and Lane’s lived experience with REDs highlights the importance of having women-led and -centered research.

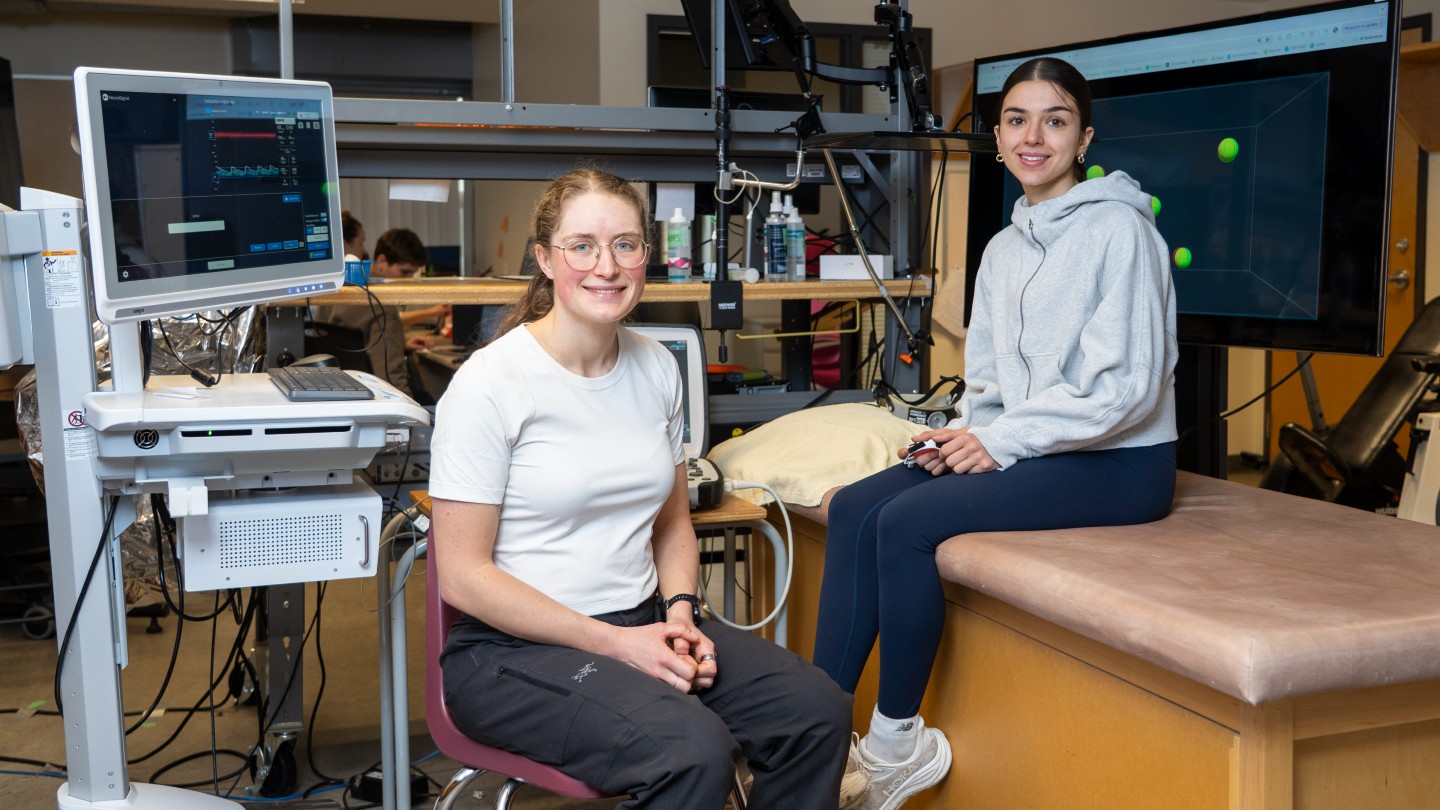

Skaug, who received $107,000 in Mitacs funding to partner with the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific as part of her PhD research, says although the reproductive health consequences of REDs are well-known, the potential impacts on cognitive function and brain-blood flow are underexplored.

Previous research shows menstrual irregularity is associated with an up to 50-per-cent increased risk in cardiovascular disease-related events later in life, but the reason why this happens is unknown. Skaug says it is crucial to investigate if menstrual irregularity also negatively impacts cerebrovascular function, which is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for cognitive impairment in later adulthood.

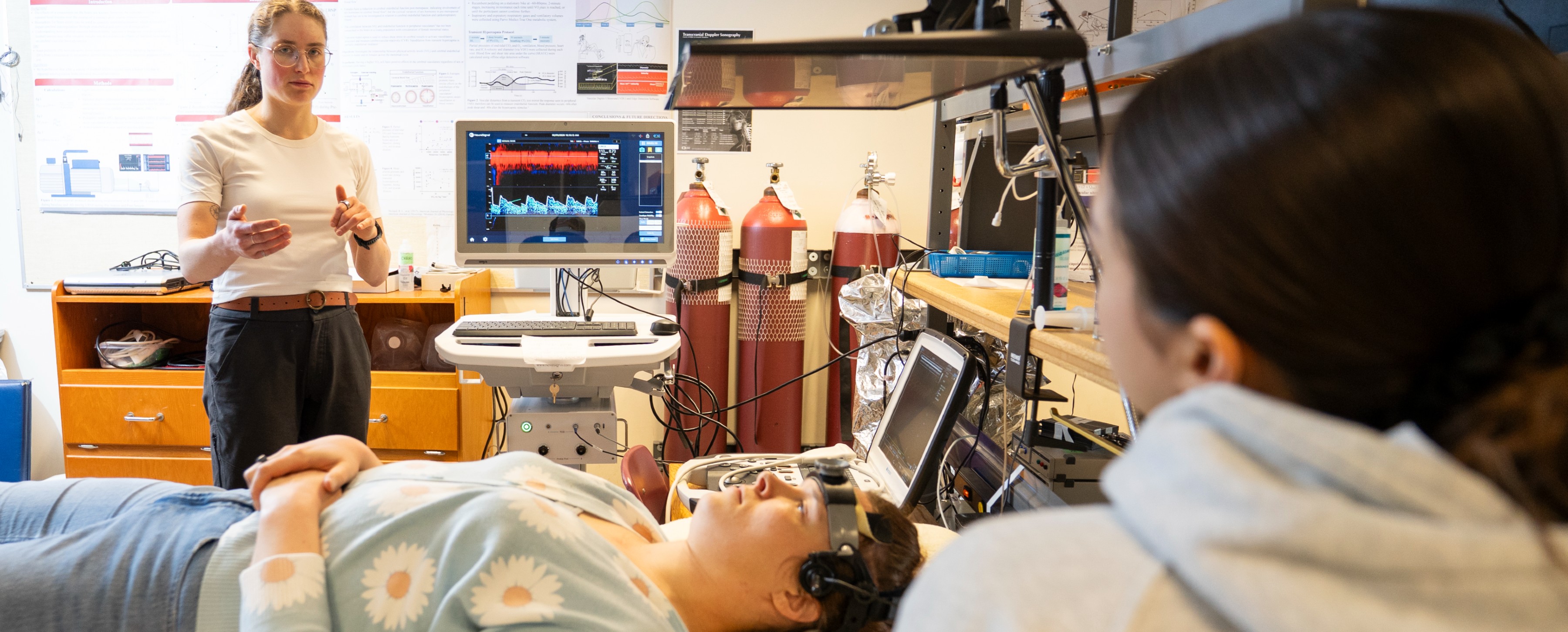

Skaug has recruited 40 participants between the ages of 17 and 40 who exercise more than three hours a week to take part in her study. After tracking their menstrual cycles for three months, the athletes complete tests that investigate regulation of blood flow in the brain.

Using ultrasound, Skaug takes images of the study participants’ arteries and measures the blood flow. Skaug wants to determine if women athletes who have lost their menstrual cycle have stiffer arteries, because of lower levels of sex hormones. She says stiffness may contribute to an increased risk of cerebrovascular dysfunction among athletes as they age.

The participants also complete a baseline assessment on Neurotracker, a cognitive training tool that challenges working memory, concentration and visual processing speed.

Skaug hopes to determine if women with irregular or no menstrual cycles due to REDs have impaired cerebrovascular function and cognitive performance.

Lane’s research builds on Skaug’s findings. Lane received a $90,000 Mitacs award, with the Feisty Media women’s health organization as the industry partner, to work on biomarkers associated with REDs.

She will analyze blood samples from the study participants for levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which is important for cognition and brain health, and irisin, a hormone secreted when exercising that is positively associated with metabolic function and bone density.

Raising awareness of REDs

The pair hope their research will help raise awareness of the seriousness of REDs.

“There’s this idea that when you lose your menstrual cycle, it’s a sign of pride or fitness or that you’re working hard enough,” Skaug says. “In reality, there are profound changes in how your body is functioning that can negatively impact your health and performance.”

Lane hopes that by furthering REDs research, they can help female athletes make more informed decisions about how to fuel their bodies, so they don’t experience what she went through as a swimmer.

“It’s important for women of all ages to understand how fueling is important for their athletic performance, and to give them motivation when those body image comparisons or societal pressures start creeping in,” Lane says.