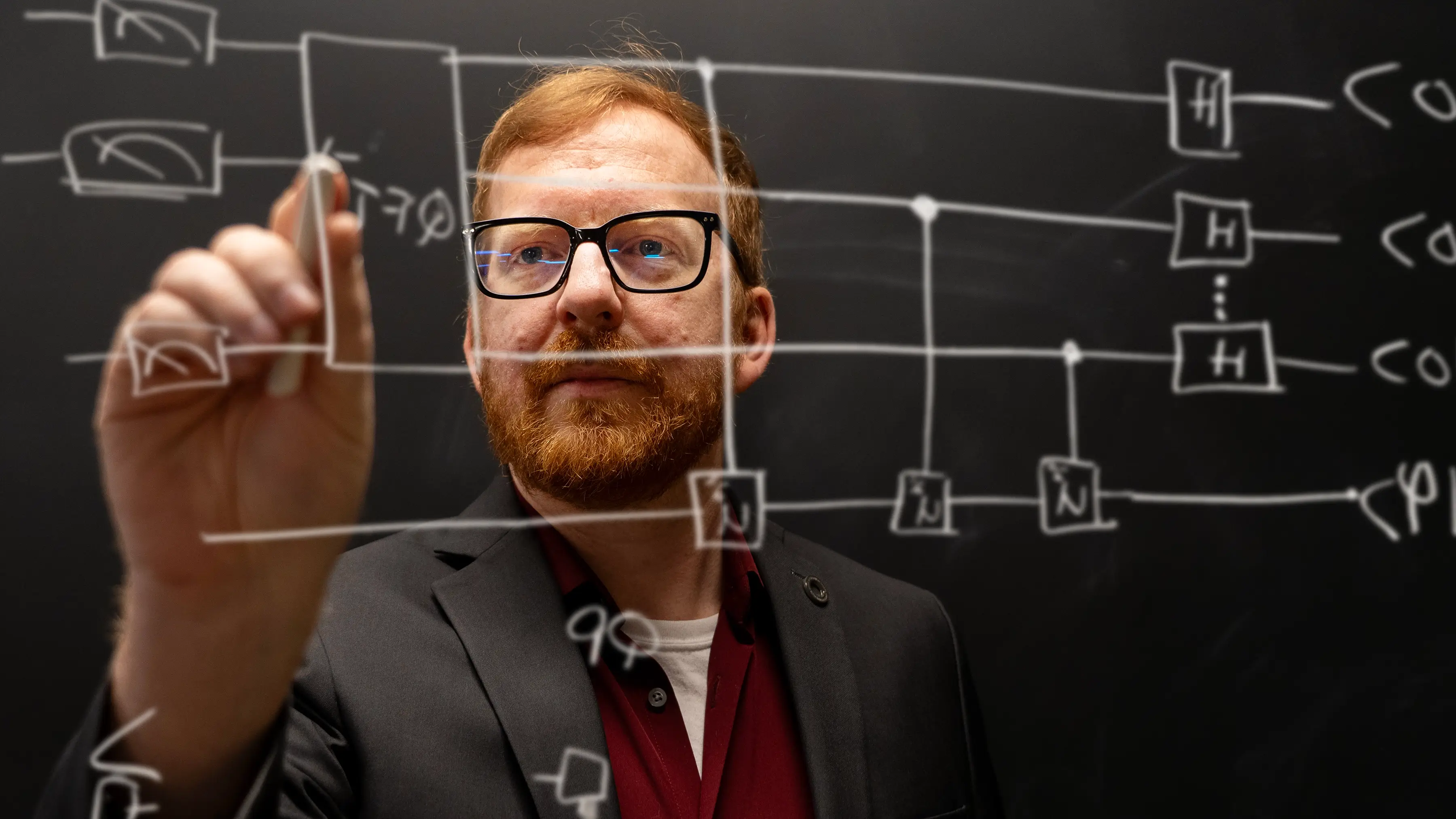

University of Victoria (UVic) physicist Dominique Trischuk studies some of the tiniest pieces of the universe, particles so small they’re invisible to even the most powerful microscopes. But while her focus is on the minuscule, her questions, and the tools she’s using to answer them, are anything but small.

“I’ve always been a hands-on person,” says Trischuk, who holds a Canada Research Chair in Particle and Astroparticle Physics. “I love figuring out how different pieces fit and work together.”

Her curiosity led her to designing scientific instruments, which quickly grew into a career in experimental physics, building tools to help scientists see what’s happening at the subatomic level. In October, Trischuk was named a Tier II CRC in Particle and Astroparticle Physics as part of the federal government’s announcement of the Canada Research Chairs program.

Transforming energy into matter

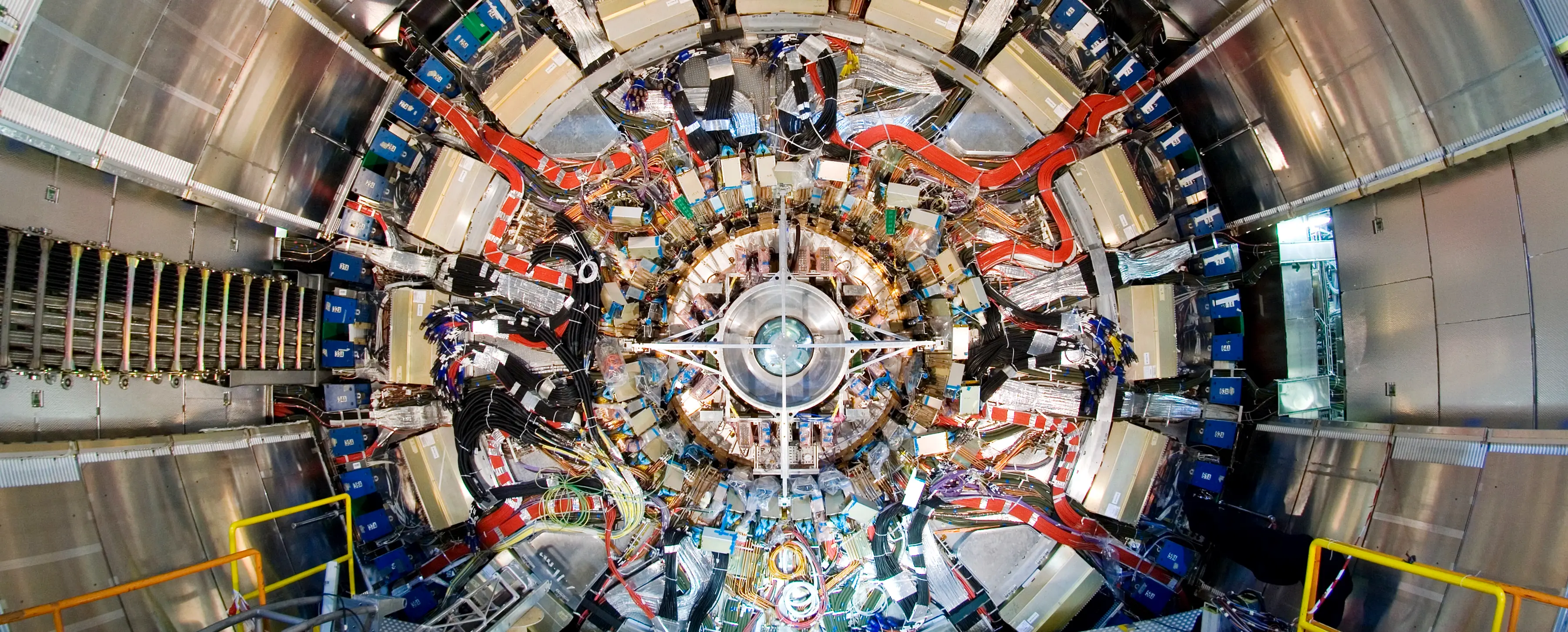

Right after her first year at university, Trischuk joined a research team creating temperature measurement systems for particle accelerators, giant machines that accelerate tiny particles to nearly the speed of light. Today, she is one of 5,500 members of the ATLAS experiment at CERN, or the European Organization for Nuclear Research, which is an international research facility in Switzerland with a 27-kilometre circular accelerator called the Large Hadron Collider. There, scientists smash trillions of protons into each other at nearly the speed of light, transforming energy into matter and producing explosions of particles that hold clues about the universe’s deepest mysteries.

Clues about dark matter

Trischuk leads a team analyzing an enormous dataset from these proton collisions, searching for rare and mysterious “long-lived particles” which, if they exist, last for only a billionth of a second but travel far enough to leave a unique signature behind.

Evidence of long-lived particles could offer important clues about dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up most of the matter in our universe but remains largely invisible,” she says. “By studying proton collisions, we can learn more about the forces and building blocks that shape everything around us.”

—Dominique Trischuk

Trischuk is also part of a team of more than 800 experts building one of the most advanced detectors ever made, designed to capture rare events with extraordinary precision. This next-generation detector, called the ATLAS Inner Tracker, has 50 times as many sensitive elements and operates 100 times faster than the previous version.

Next breakthroughs in particle physics

Building this new detector is a monumental task. Trischuk is leading the development of a data collection system that can measure the trajectory of particles to within 20 microns, less than half the width of a human hair.

The detector is being built and tested above ground before being installed deep beneath the surface at CERN, where it will help scientists capture detailed images of particle collisions over the next decade.

“Seeing this detector come to life will be incredibly exciting,” Trischuk says. “It will mark a major leap forward in our field and open a door for the next breakthrough in particle physics.”